A three-strip Technicolor camera. Museum of the Moving Image. Queens, New York. (Photo by Marcin Wichary. Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0])

In the early 20th century, motion pictures and cinemas were just getting started. Thousands of large, comfortable theaters appeared by 1915. New multi-reel feature films were imported from Europe and embraced by the American middle-class. Many legendary studio names date from these early days—Universal (1912), Goldwyn (1916), and Fox (1915) were founded as part of the movie boom. By the 1920s, the lead actors of silent films were movie stars in the modern sense—well-paid and nationally recognized. “The movies” had quickly become an important part of American cultural life.

Beginnings of Technicolor

Since the advent and public introduction of film, audiences were used to seeing everything in black and white. That began to change in the early 20th century when Technicolor entered (and arguably disrupted) the world of black and white films.

At that point, limited color technology existed for motion pictures. Motion picture strips could be carefully dyed, creating a color cast over certain frames; meanwhile, others were painted by hand. However, another process known as Kinemacolor was introduced in a 1908 trial film. It projected images onto a movie screen through colored filters. However, only red and green filters were used, limiting the color range produced. The projecting equipment was also quite costly.

A surviving frame from The Gulf Between Them (1917). (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Early Success in Hollywood

Films of the 1920s started to change the course of the medium forever with the advent of two new additions—sound and color. Synchronized dialogue was introduced, disrupting the silent film industry, and the first full-color feature films were also realized at this time. Neither change to the industry was immediately accepted by all, though. Filmmakers and actors expressed concern that color and sound could become garish and distract from the storytelling.

Technicolor's true breakthrough arrived in 1922. Filmed using the prism and filter method to split red and green light onto two film reels, a color transfer process was invented to create one colorful final reel. Each of the two reels would be toned red or green, with gradients and shade. The two reels would then be glued together to form one strip which combined the colors in each slide. All that was required to project a color image was the standard white light already used in theaters.

Despite the refinement of this ground-breaking development, the Technicolor process was expensive. Films in the 1920s that chose to use color often confined the expensive process to just a few scenes—often weddings or dance numbers.

Scan of a 35 mm Technicolor film strip from The Phantom of the Opera (1925). (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

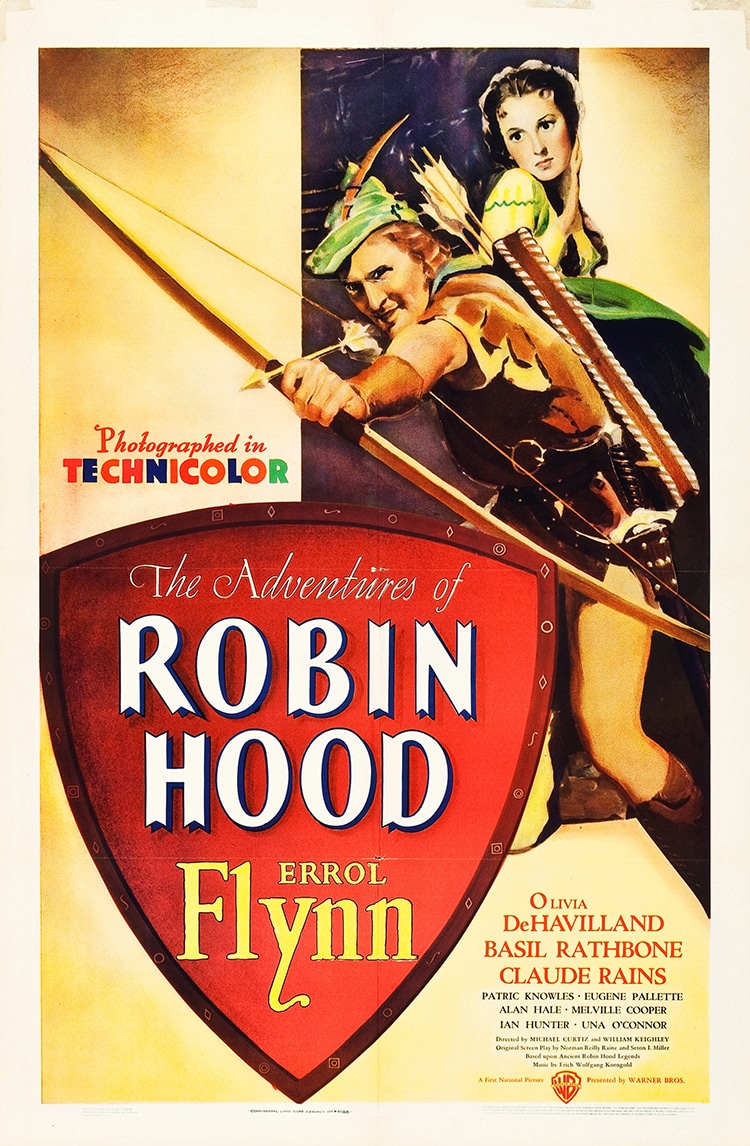

Poster for The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) citing use of Technicolor process. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

The Appeal of Color Films

The dye-transfer process cemented Technicolor's domination of color film for over two decades. Gone With The Wind (1939), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), and Disney's Snow White (1937) all used the process. Technicolor also received credit for The Wizard of Oz in 1939. The film, directed by Victor Fleming, had many of its classic elements dictated by the requirements of the Technicolor process. In fact, the iconic ruby slippers were originally silver, but producers decided the jewel tone would appear better. Horses were also dyed with Jello powder to produce vibrant hues. Technicolor employees were on set to ensure best results. So much studio lighting was used that temperatures could rise over 100 degrees on set.

The Wizard of Oz marked a shift in how filmmakers and the general public related to color. In the beginning, Dorothy lives in sepia-toned Kansas. Sepia was representative of a country only just emerging from the Great Depression and Dust Bowl era, but the filming was actually not in black and white. The entire set—and Dorothy's costumes—were created in sepia tones. When Dorothy steps out of her tornado-blown house into Oz, a sepia-covered body double gazes out in wonder. She then steps aside, and a colorfully costumed Judy Garland emerges. The early worries of filmmakers that color might distract the audience proved incorrect. Color became part of the story itself and an important narrative device.

Scene shot in Technicolor from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) starring Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russel. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Competition and Innovation

Technicolor's dominance in color film production went virtually unchallenged until the 1950s. Color movies had become much more popular, and cheaper processes became available. “Color by Technicolor” remained the gold standard, but Eastmancolor by Kodak and Anscocolor by Ansco offered cheaper filming alternatives. Rather than three reels, these methods required only one reel of triple-emulsion film. To remain relevant, Technicolor capitalized on its superior colors and clarity. The company began converting movies shot on other brands of film to Technicolor reels ready for distribution. In an example of corporate foresight, Technicolor remodeled its bulky three-strip cameras to film in the popular wide-screen cinema format. Technirama offered high-quality, compressed color images that could be expanded through projection.

After an almost 50-year run, Technicolor's dye-transfer process finally phased out of use in the 1970s. However, during the 1980s the company popularized a “silver-retention” chemical process for film known as ENR. Many modern directors have used the process, and it can be seen in films such as Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan. With filming being digital in modern studios, Technicolor in the 21st century has restored old films and entered multiple arenas of digital media. The company that came to define bold, brilliant color remains a household name.

Legacy

Spearheaded by Technicolor, the development of color motion pictures spanned three generations of movie goers. The rapidly shifting technology of cinematography often visibly dates films, provoking nostalgia or amusement at technologies past. Technicolor influenced American movies for a century and the company's name has evolved beyond itself. The continued use of “technicolor” as a descriptor of all things vibrant and colorful is a testimony to the lasting impact of their technology on the American cultural lexicon.

Poster for Singin' in the Rain (1952). Technicolor was popular for musicals from its early days. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Learn more about Technicolor and The Wizard of Oz.

Related Articles:

Rainbow Labyrinth Light Installation Immerses Visitors in a Technicolor World

Love a Colorful Challenge? Try This 1,000-Piece CMYK Puzzle!

5 Pioneers of Early Animation Who Influenced the Future of Film

Restored Film Footage Shows What Life Was Like in New York City Over 100 Years Ago