Celebrated for their one-of-a-kind process and distinctive aesthetic, woodblock prints have become a widely recognized and iconic form of Japanese art. Along with paintings, prints produced from the 17th century through the 19th century captured the spirit of ukiyo-e, a genre that presented “pictures of the floating world” to the public.

Here, we explore these Japanese woodblock prints, paying particular attention to their fascinating history, age-old techniques, recognizable style, and lasting legacy.

History of Woodblock Printing

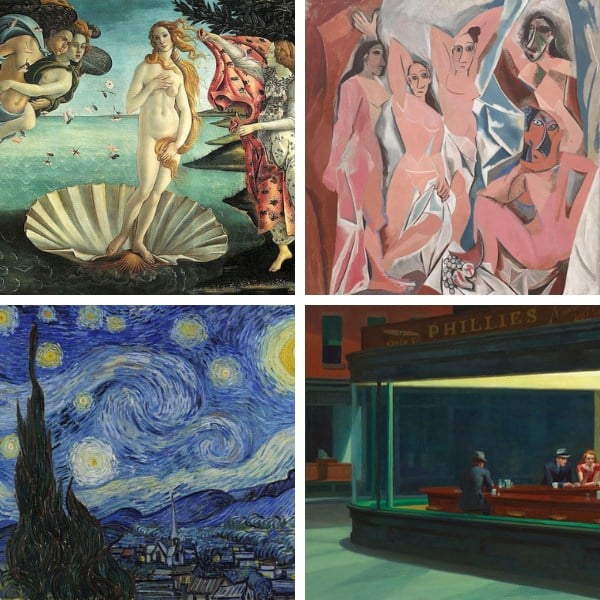

Katsushika Hokusai, “The Great Wave off Kanagawa,” ca. 1829-1833 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Introduced during China's Han Dynasty, which lasted from 206 BCE to 220 CE, the art of woodblock printing was not popularized in mainstream Japan until its Edo period, an era denoting 1603 through 1868. Initially, the woodblock printing process was used to reproduce traditional hand-scrolls as affordable books. Soon, however, it was adapted and adopted as a means to mass produce prints.

While woodblock printing was eventually replaced by methods of moveable type (in terms of text), it remained a preferred and popular method among Japanese artists for decades—namely, those working in the ukiyo-e genre. Japanese masters like Andō Hiroshige, Katsushika Hokusai, and Kitagawa Utamaro helped elevate the practice with their “floating world prints,” which are considered world-class works of art today.

Technique

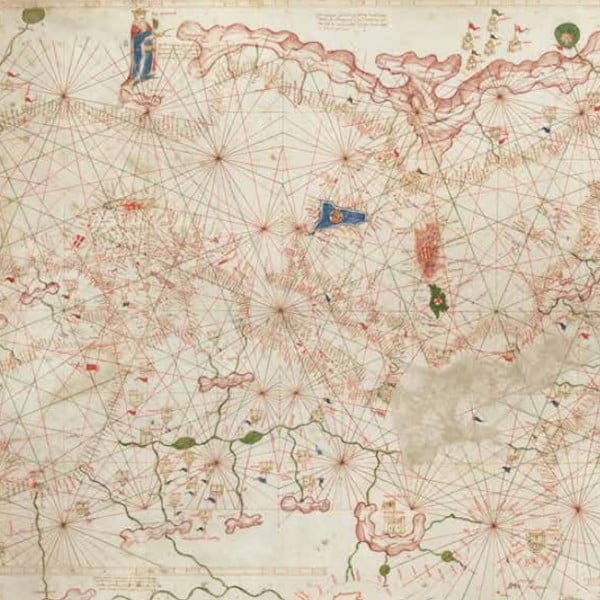

Much like western woodcut processes, the Japan-based method revolves around relief carvings and conscious color application.

To create a woodblock print in the traditional Japanese style, an artist would first draw an image onto washi, a thin yet durable type of paper. The washi would then be glued to a block of wood, and—using the drawing's outlines as a guide—the artist would carve the image into its surface.

The artist would then apply ink to the relief. A piece of paper would be placed on top of it, and a flat tool called a baren would help transfer the ink to the paper. To incorporate multiple colors into the same work, artists would simply repeat the entire process, creating separate woodblocks and painting each with a different pigment.

Stylistic Characteristics

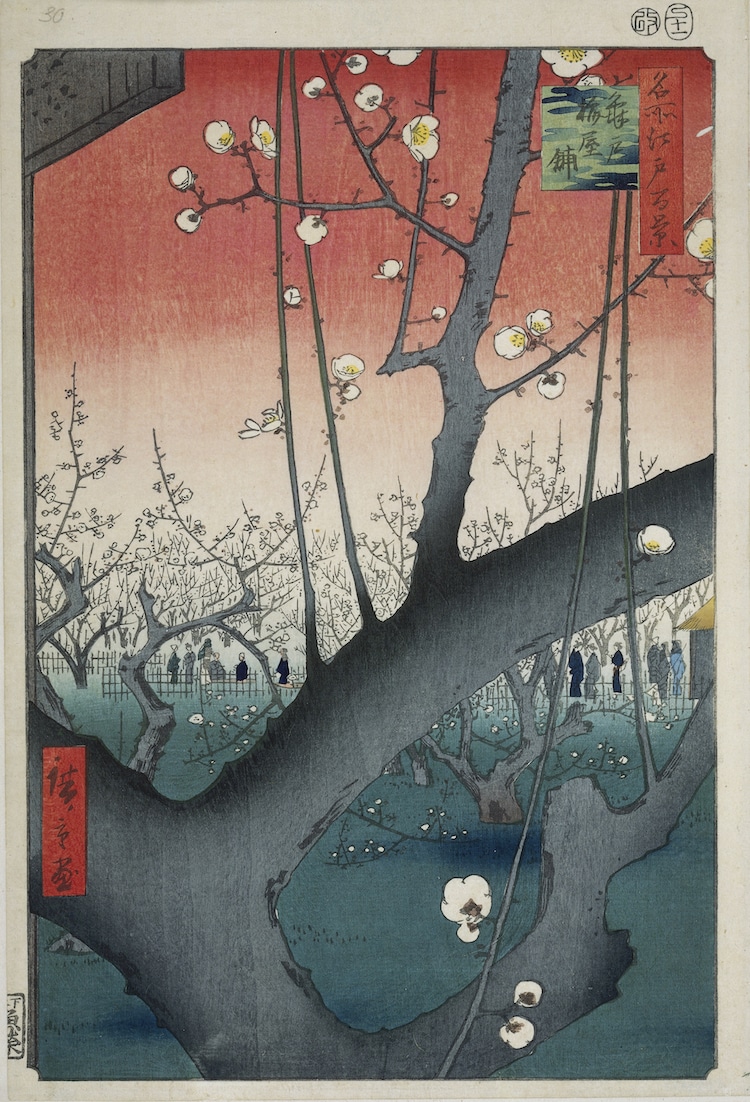

Andō Hiroshige, “The Plum Garden in Kameido,” 1857 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Rich Color Palette

While producing prints was a quick and seemingly mechanical process, it culminated in rich hues reminiscent of meticulously hand-colored paintings. Radiant reds, vivid blues and greens, and even stark blacks are prevalent in the most celebrated woodblock prints, like Hiroshige's The Plum Garden in Kameido.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, these impressive color palettes were first evident in pieces produced during the late 1700s, when artists advanced their processes with new tools and materials. “To print with precision using numerous blocks on a single paper sheet, a system of placing two cuts on the edge of each block to serve as alignment guides was employed. Paper made from the inner bark of mulberry trees was favored, as it was strong enough to withstand numerous rubbings on the various woodblocks and sufficiently absorbent to take up the ink and pigments. Reproductions, sometimes numbering in the thousands, could be made until the carvings on the woodblocks became worn.”

Flat Compositions

Torii Kiyonaga, “Bathhouse Women,” ca. 1780 (Photo: Library of Congress )

While most artists working with paper aim to achieve realistic senses of perspective, those specializing in woodblock prints were less concerned with depth and dimensionality. Instead, they favored strong shapes, graphic designs, and bold lines.

This stylistic preference is evident in Kiyonaga's Bathhouse Women, where the artist's preference for pops of color, beautiful subject matter, and even compositional geometry dominate any interest in achieving accurate perspective.

Bold Lines

Andō Hiroshige, “Kanbara,” ca. 1833-1834 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Given the nature of the printmaking process—especially when prints were monochromatic—thick, obvious outlines were both inevitable and embraced aesthetic features.

These exquisite black lines contrasted the colorful, watercolor-like nature of the paints, giving the pieces an illustrative quality and emphasizing their flat nature. “The soft, water-soluble colors, which were until the late nineteenth century derived from plant and mineral sources, were applied in relatively large flat areas bordered by the fine line drawing of the design,” explains San Francisco's Asian Art Museum. “Even when artists borrowed shading techniques from the West, the woodblock process still created an essentially flat image, one of the special characteristics of Japanese prints.”